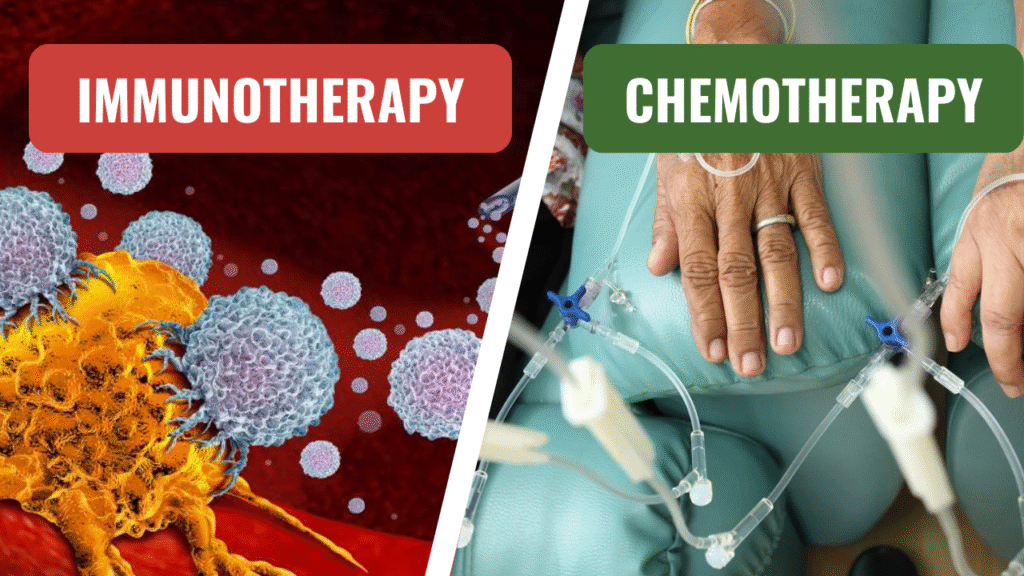

Cancer treatment has evolved significantly, from broad and aggressive methods to a diverse range of ‘targeted’ and innovative therapies. Two of the most discussed options today are immunotherapy and chemotherapy. Both are designed to combat cancer, but they do so in distinct ways, each with advantages and challenges. In this piece, we explore how these treatments could potentially revolutionize cancer care, their mechanisms, side effects, and the implications for the future of oncology. Whether you’re a patient, caregiver, or simply curious, this guide can give you a deeper understanding of these two powerful tools in the fight against cancer.

Cancer treatment has evolved significantly, from broad and aggressive methods to a diverse range of ‘targeted’ and innovative therapies. Two of the most discussed options today are immunotherapy and chemotherapy. Both are designed to combat cancer, but they do so in distinct ways, each with advantages and challenges. In this piece, we explore how these treatments could potentially revolutionize cancer care, their mechanisms, side effects, and the implications for the future of oncology. Whether you’re a patient, caregiver, or simply curious, this guide can give you a deeper understanding of these two powerful tools in the fight against cancer.

What Is Chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy has been a fundamental weapon in the fight against cancer for many years. It harnesses powerful drugs, also known as cytotoxic drugs, to kill rapidly dividing cells — cancer’s calling card. These drugs circulate in the bloodstream, attacking the cancer cells wherever they are. But it’s not a selective method. And healthy cells that also divide fast, such as in your hair follicles, bone marrow, and digestive tract, can become trapped in the crossfire.

Chemotherapy is usually given in cycles, which allow the body to recover between doses. It is used against a wide range of cancers — from breast and lung cancer to leukemia — and can be administered as a first treatment, a post-surgery intervention, or a way to shrink a tumor before other treatments.

What Is Immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy, meanwhile, is a more recent addition to the cancer care landscape, widely seen as a coup. Rather than killing cancer cells directly, it turbocharges your immune system to do the job. Your immune system is your body’s built-in defense force, but cancer cells are sneaky — they can either hide from it or tamp it down. Immunotherapy fills the gap by hiking into the cancer cells beneath the immune system’s ability to see or teaching the immune system to see and wipe out cancer wherever it lurks.

Several types of immunotherapy include checkpoint inhibitors, CAR T-cell therapy, and monoclonal antibodies. It has been especially hopeful for cancers like melanoma, lung cancer, and a few blood cancers, giving hope where traditional therapies have offered little.

How Do They Work Differently?

In approach, they are different. Chemotherapy is a sledgehammer — it knocks out both cancer cells (and some healthy ones) with brute force. Immunotherapy is a strategist — it teaches your body’s natural defenses to recognize and precisely destroy cancer.

Chemotherapy: Kills rapidly dividing cells with drugs such as cisplatin or doxorubicin. It’s systemic — it works throughout your body — and can start shrinking tumors in days.

Immunotherapy: Relies on agents such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or nivolumab (Opdivo) to remove cancer’s “invisibility cloak” or to engineer immune cells to assault tumors. It is more of a targeted approach but can take a while.

This has everything from treatment timelines to side effects to long-term outcomes.

Effectiveness: Which Wins?

It also depends on the type and stage of cancer and the patient. Chemotherapy is a known workhorse — it works for many, many cancers and can be curative for some, like testicular cancer or early-stage breast cancer. However, it tends to be less effective against late-stage cancers or when the cancer evolves to resist drugs.

And so, for some situations, immunotherapy works. For example, checkpoint inhibitors have changed how melanoma is treated, with some patients entering remission that can last for years. CAR T-cell therapy has produced jaw-dropping results in blood cancers like lymphoma, especially when traditional treatments could not help. But it’s not a one-size-fits-all response — some cancers respond, and research has been going on in hopes of expanding the treatment to more forms of cancer.

In other words, neither is “better” in general. Doctors frequently use them in combination or adjust the regimens based on a patient’s particular profile, capitalizing on chemotherapy’s quick effects and immunotherapy’s potential for lasting impact.

Side Effects: What to Expect

Each has side effects, but they are not the same.

Chemotherapy: As it also kills all fast-growing cells, it causes side effects, including hair loss, nausea, fatigue, and a compromised immune system (which increases the risk of infection). Those are usually mild ones that come out and fade after treatment stops.

Immunotherapy: Side effects are related to an overly activated immune system, leading to inflammation that could include rashes, fever, or even colitis. Often less severe than chemo’s, they can linger or very occasionally turn severe if the immune system goes on to assault healthy organs.

Advertisement Patients frequently say that chemotherapy feels like a sprint — intense but time-limited — while immunotherapy feels more like a marathon, with subtler but longer-lasting effects.

Cost and Accessibility

Cancer treatment is not free, and both gestures speak to that. Chemotherapy can cost wildly different amounts, depending on the drugs and duration, frequently from $10,000 to $100,000 a course. It’s widely available, however, as a longstanding therapy.

Immunotherapy tends to be more expensive, particularly the more advanced varieties like CAR T-cell therapy, which can cost more than $400,000 for a single treatment. Insurance coverage is better, though access is lacking in some areas, and not all hospitals provide them. This chasm lays bare a dilemma in the “new era” of cancer care: Curb the costs of increasingly advanced cancer treatment without stifling innovation.

The Future of Treating Cancer

Chemotherapy, with its reliability and adaptability, is not likely to be replaced anytime soon. However, immunotherapy represents a shift towards personalized medicine. Researchers are exploring potential combinations, such as pairing checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy, to enhance their effectiveness. Clinical trials are also beginning to unlock the potential of immunotherapy for a broader range of cancers and to refine the criteria for identifying those most likely to benefit from it.

The ultimate goal is a world where cancer is not a death sentence but a manageable chronic condition. The ability of immunotherapy to create ’memory’ in immune cells, potentially preventing a recurrence, brings us closer to this vision.

Which Is Right for You?

There’s no simple answer. Cancer type, stage, genetic markers, and overall health help determine the recommendation. Some patients do well with the targeted precision of immunotherapy; others require the wholesale assault that chemotherapy delivers. It’s often “not ‘versus’ but ‘together’ — we’re a tag team to beat cancer.”

Discuss testing with your oncologist, such as PD-L1 levels for immunotherapy, and consider the possible benefits and risks. It’s your trip, and the ability to comprehend these options enables you to have a say in the plan.

FAQs on Immunotherapy vs. Chemotherapy

Is it now possible to do without chemotherapy and rely entirely on immunotherapy?

Not yet. Although revolutionary, immunotherapy doesn’t help all cancers or all patients. Chemotherapy is still necessary for its broad reach, with the two frequently used in combination for a combined or “additive” benefit.

Which treatment has less of a side effect?

It varies. The side effects of chemotherapy (like nausea and hair loss) are generally predictable and severe but sometimes temporary. However, the side effects of immunotherapy (inflammation, fatigue) can be less severe and more persistent, or, rarely, intense, when the immune system overreacts.

How long does a treatment last?

Chemotherapy is administered in cycles — ranging from weeks to months, depending on the regimen. The immunotherapy might require fewer treatments and can go on for months or longer, particularly for maintenance.

Can you get immunotherapy only if you have advanced cancer?

No, although it is frequently employed when cancer has advanced, or other treatments have failed. It’s being considered sooner, especially in cancers like melanoma or lung cancer that have specific markers.

Why does immunotherapy cost so much?

It is cutting-edge — the process of creating drugs like CAR T-cells is complicated, engineering and personalizing, and expensive. The scale of research and limited production are also significant.

Can lifestyle modifications reinforce either treatment?

A good diet, exercise, and stress management can help your body through both, but they won’t directly boost the drugs. As always, consult with your doctor before making any changes.

And: How successful is each?

Success varies by cancer. Chemotherapy also cures some early-stage cancers (e.g., >90% for testicular cancer), and immunotherapy leads to a remission rate of 20-40% of patients with advanced melanoma. Results may vary per individual.

Conclusion

The two seem like chapters in the ever-evolving tale of cancer, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy. The inheritance of chemotherapy is its reliability —a blunt instrument, but it does help. Immunotherapy promises to be a game-changing therapy and a new era in our war against this disease. Combined, they are hopeful, choiceful, and progressive. As science progresses, the “versus” becomes “and” to treatments as diverse as the people they serve.

If you’re weighing this decision, trust your medical team and keep yourself informed. The right path is a path that fits your fight.

Table of Contents

SEARCH HERE

CATEGORIES

RECENT POST

Advanced Mitochondrial Formula 2025: Can It Truly Recharge Your Energy Levels?

The Truth About Aquaponics 4 You (2025): Does It Actually Work?

Hepato Burn Supplement Review: What You Need to Know Before Buying

“The Ultimate Guide to Papillex: Natural Immune Support for HPV Relief”

Slim Down Naturally: The Truth About Plant-Based Fat Burner That Actually Work

TedsWoodworking Review 2025: Is It Worth It for Your DIY Projects?

“Immunotherapy vs. Chemotherapy: A New Era in Cancer Treatment”

“The Ultimate Guide to Hyperpigmentation Laser Treatment in 2025”

Is UV 7 Good for Tanning? What You Need to Know Before You Glow

Planning a Trip from New Windsor to Grand Canyon? Here’s What to Know

“Your Guide to the Closest Airports to Yosemite National Park”

“How to Create the Perfect Gluten-Free Chicken Soup for Cold Days”

“The Secret to Authentic Creole Sauce: Step-by-Step Recipe”

“Natural Weight Management Made Easy: Exploring Nagano Tonic”

Can Rosemary Oil Reverse Male Pattern Baldness? The Truth Revealed

ProvaDent Reviews & Complaints: Is This Supplement the Real Deal for Oral Health?

“Everything You Need to Know Before Buying the Clawsable Heated Cat House”

“Are Ryan’s Shed Plans Worth It? A Practical Guide for DIYers”

“Miracle Massage Wand and More: Exploring the Ageless Knees Method”

BV No More by Jennifer O’Brien: A Simple, Natural Approach to Tackling Bacterial Vaginosis (BV)

Unlock Your Dog’s Full Potential: A Complete Review of Brain Training for Dogs

“Neotonics Reviews: Pros, Cons, and What You Need to Know Before Buying”

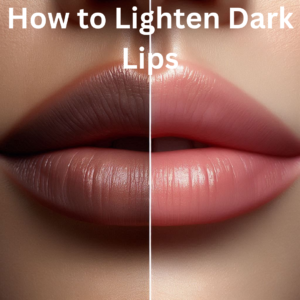

“How to Lighten Dark Lips: Top Lip Lighteners and Remedies”

“Are Seed Probiotics Safe? A Look at Potential Side Effects”

“Liver Detox Juice: Ingredients, Benefits, and How to Make It”

“Rejuvenecimiento Facial: Transform Your Skin and Boost Your Confidence”

Everything You Need to Know About Field Roast Pepperoni: Taste, Texture, and Uses

Mini Bernedoodles: Health, Care, and Training Tips for New Owners

Exploring the Best Vegan Collagen Supplements for Healthy Aging

“Beyond Muscles: The Surprising Ways Creatine Boosts Your Health”